- You need three things to launch: Terms of Service, privacy policy, and clear pricing—everything else can come later

- Your SLA should define response times, turnaround times, and revision limits that match your service tiers

- One ToS with proper jurisdiction and GDPR clauses works for international clients—no country-specific contracts needed

You’ve built your productized service. Packages are defined, pricing is set, and clients can buy directly from your website. But when it comes to legal documentation, you’re probably still operating like a traditional agency—negotiating custom contracts, rewriting scope for each client, and wondering if your Terms of Service actually protect you.

Here’s the problem: traditional agency contracts assume every engagement is different. Custom scope, custom pricing, custom terms. That model breaks when you’re selling the same package to fifty different clients.

Productized services have more in common with SaaS businesses than with agencies. You’re selling access to a defined service at a fixed price, often on a recurring basis. Your legal framework should reflect that. One set of terms that covers everyone. Clear service levels tied to each tier. Boundaries that hold up when a client asks for “just one more thing.”

This guide covers the legal infrastructure that actually fits the productized model: Terms of Service that work for self-service purchases, SLAs that protect your delivery capacity, IP clauses that keep your processes yours, and compliance basics for international clients. No law degree required—just practical frameworks you can implement this week.

Why productized services need different legal infrastructure

Traditional agencies operate on a simple premise: every client is different, so every contract is different. You scope the work, negotiate terms, sign an MSA, attach a Statement of Work, and repeat the process for the next client. It works, but it doesn’t scale. If you’re still figuring out how to productize a service, start with the implementation guide—then come back for the legal setup.

When you productize, you’re making a different promise. You’re saying: “Here’s exactly what you get, here’s exactly what it costs, and here’s exactly how it works.” The client doesn’t negotiate scope. They pick a package and buy it.

That shift changes everything about how your legal documents should function. If you have existing agency clients, you’ll need to transition them to your productized model—which includes getting them onto your new terms.

The shift from custom contracts to standardized terms

In a traditional agency, your contract is a negotiation tool. Clients redline your MSA, request changes to payment terms, push back on liability clauses. You spend hours on each deal, and your “standard” contract becomes anything but standard.

Productized services flip this model. Your Terms of Service become a take-it-or-leave-it document—like the terms you agree to when signing up for any SaaS product. Clients accept them by purchasing. No negotiation, no redlines, no back-and-forth with their legal team.

If you spend three hours negotiating contract terms for a $500/month package, you’ve already lost money on that client.

The goal: one set of terms that every client agrees to, covering every package you sell.

What productized services share with SaaS

Christopher Lyle, who runs KickSaaS Legal, puts it this way:

SaaS contracts focus on access and data security, distinct from traditional contracts that emphasize physical product delivery.

Christopher Lyle,

KickSaaS Legal

Christopher Lyle,

KickSaaS Legal

Productized services sit in similar territory. You’re not delivering a one-time project with a defined end date. You’re providing ongoing access to a service—often with recurring billing, usage limits, and defined service levels.

Like SaaS | Unlike SaaS |

|---|---|

Subscription billing (auto-renewal, cancellation terms) | Human delivery, not just software |

Standardized terms for all clients | Clients expect to own what you create |

Defined response times and turnarounds | Constant scope pressure ("can you also do X?") |

Tier-based usage limits |

Your legal framework needs to handle both: the scalable, SaaS-like purchase flow and the human-delivered, scope-sensitive reality of service work.

Implementation checklist

You don’t need perfect legal infrastructure to launch. You need enough to protect yourself and your clients while you grow. Here’s how to prioritize.

Minimum viable legal setup for launch

Before you take your first paying client, you need:

Terms of Service: A single document covering service descriptions, payment terms, IP ownership, liability limits, and termination. This is non-negotiable. Even a basic ToS is better than handshake agreements.

Privacy Policy: Required if you collect any personal data (you do—at minimum, client names and emails). Also required to run most ad platforms or payment processors.

Clear pricing and scope: Your sales page copywriting should make it obvious what each package includes. This isn’t a legal document, but clarity here prevents disputes later.

That’s it for launch. Three things.

What you can add later:

formal SLA documentation

Data Processing Agreement for EU clients

separate contractor agreements (once you bring on help)

service credits policy

detailed security documentation

Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. A productized service with a basic ToS is better positioned than an agency with no written agreements at all.

When to invest in custom legal review

Template ToS documents work for most early-stage productized services. But there’s a point where custom legal work makes sense.

Consider hiring a lawyer when:

you’re crossing $20–30k/month in revenue (you have something worth protecting)

you’re entering regulated industries (healthcare, finance, legal services)

you’re handling sensitive data (PII, financial records, health information)

enterprise clients are requesting custom terms (and you want to accommodate them)

you’ve had a dispute or near-miss that exposed gaps in your terms

you’re preparing for acquisition (investors will review your contracts)

Don’t ask a lawyer to “write your contracts.” Ask them to review your existing terms and identify gaps. Bring them your current ToS, your service descriptions, and a list of specific questions. You’ll get better results and a smaller bill.

A good review for a productized service might cost $1,500–3,000 depending on complexity and the attorney’s rates. Specialized attorneys who understand SaaS and productized models (like KickSaaS Legal or similar firms) will move faster than generalists.

Template resources and where to start

You don’t need to write your ToS from scratch. Several resources offer templates designed for digital services and productized businesses:

Free starting points:

Stripe Atlas provides basic Terms of Service and Privacy Policy templates for startups

many website builders (Shopify, Squarespace) include basic policy generators

open-source templates exist on GitHub, though quality varies

Paid templates ($50–500):

Search for “productized service agreement template” or “subscription services contract.” Look for templates designed for recurring services, not one-off projects. Vet any template against the list below before buying.

What to look for in a template:

written for services, not products or SaaS

includes subscription/recurring billing language

covers IP ownership and assignment

has clear scope and revision limits

updated recently (legal requirements change)

For a real-world example, Mimi Zhou’s productized services terms shows how a copywriting consultant structures her ToS—each service tier with specific deliverables, clear no-refund policy, and payment required before work begins.

What to customize:

Even the best template needs adaptation. At minimum, update your company name, service descriptions, payment terms, turnaround times, and jurisdiction. Read through the entire document and make sure every clause reflects how your business actually operates.

The rest of this guide breaks down each component in detail. If you’re just launching, the checklist above is enough. Come back to these sections as your service grows.

Terms of service: your foundation document

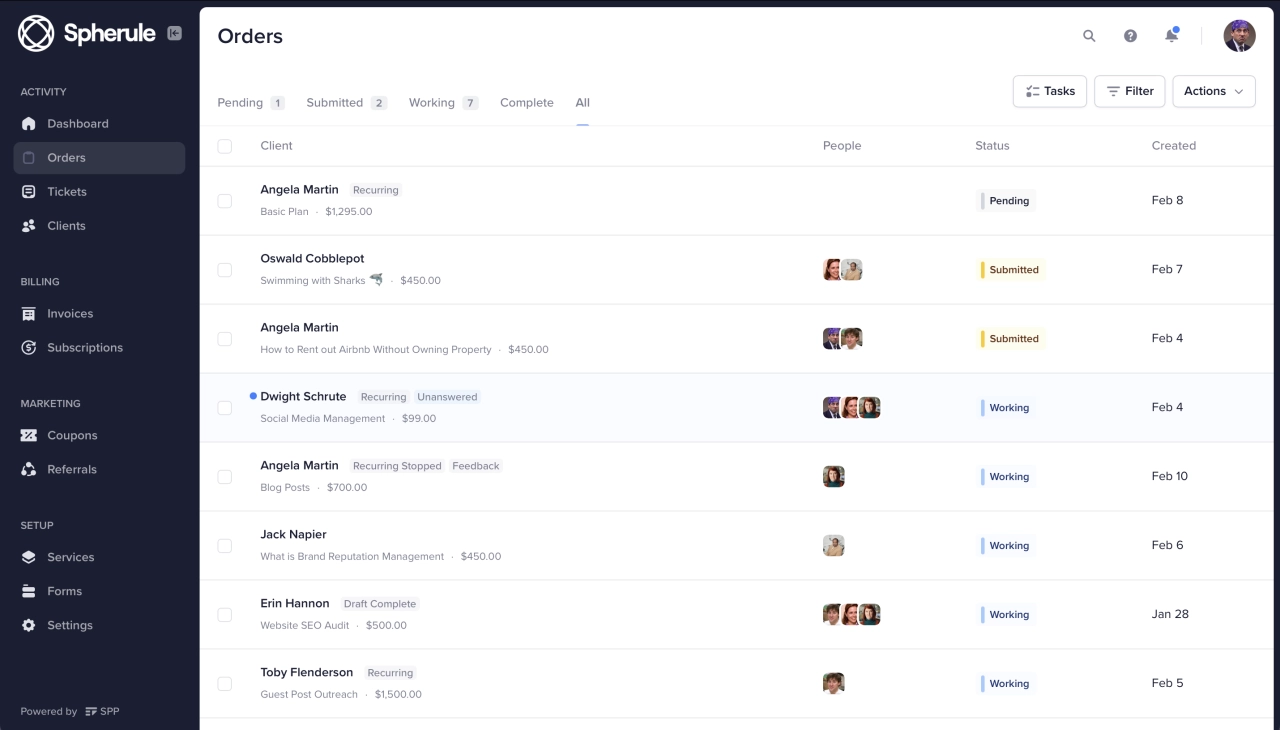

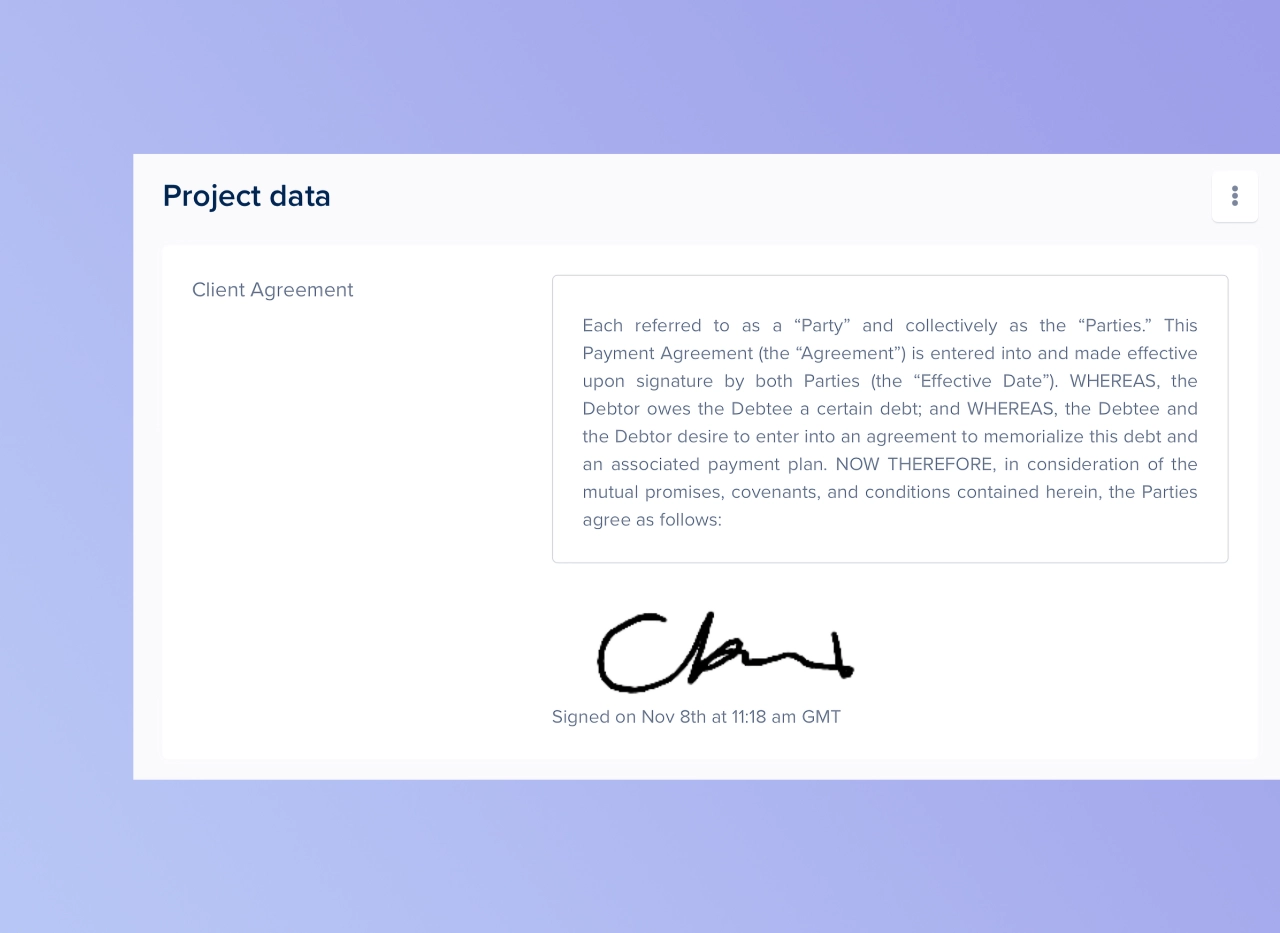

Most clients accept your ToS by checking a box at checkout. But if you’re selling higher-value packages or want extra protection, you can require a signature before purchase. SPP’s order forms include a signature field that captures the client’s signature, timestamp, and IP address—all appended to the project record.

Collect signatures to prevent invoice disputes.

Whether you use a checkbox or a signature, your Terms of Service needs to do a lot of work upfront.

Erin Austin, an IP attorney at Think Beyond IP, warns:

Don’t leave anything to chance regarding terms that are the difference between a profitable and an unprofitable productized service, such as scope of work, number of revisions, ownership of deliverables, refunds, and deadlines.”

Erin Austin,

Think Beyond IP

Erin Austin,

Think Beyond IP

Courts have found that a simple link to your terms isn’t enough—you need explicit language like “By clicking Buy, you agree to the Terms & Conditions.

Essential clauses for package-based services

Every productized service ToS needs to cover these fundamentals:

Clause | What it covers |

|---|---|

Service description | What you’re providing (and what you’re not) |

Payment terms | When payment is due, what happens if it fails, refund policy |

Intellectual property | Who owns the deliverables, who owns your processes |

Limitation of liability | Caps on what you’re responsible for if things go wrong |

Termination | How either party can end the relationship, what happens to work in progress |

Governing law | Which jurisdiction’s laws apply, where disputes get resolved |

The specifics matter less than having clear language that matches how your business actually works. A ToS written for a traditional agency—with references to “projects,” “estimates,” and “change orders”—will confuse clients buying fixed packages. We’ll cover service descriptions, payment terms, IP, and termination in detail below. For limitation of liability, start with a template and have a lawyer review—this clause varies too much by business type and jurisdiction to give universal example language.

Service descriptions and deliverable definitions

This is where most productized services get sloppy. Your sales page says “4 blog posts per month” but your ToS says “content creation services.” When a client expects 2,000-word articles and you deliver 800-word posts, that vague language won’t protect you.

Be specific:

Quantity: How many deliverables per billing period.

Format: What form the deliverables take (word count ranges, file formats, etc.).

Timeline: When clients can expect delivery.

Inputs required: What you need from the client to do the work (submit intake form, provide assets, etc.).

Quality standard: What “done” looks like (rounds of revision, approval process).

A design subscription might specify: “Up to 2 active design requests at a time. Each request receives one initial concept plus up to 2 rounds of revision. Average turnaround is 2-3 business days per request. Requests are worked in queue order.”

That language sets clear expectations. When a client asks why their fifth request hasn’t started, you can point to the “2 active requests” limit.

Revision limits and what’s “out of scope”

Scope creep kills productized margins faster than almost anything else. Your ToS is your first line of defense.

Define revisions explicitly. “Two rounds of revision” is clear. “Reasonable revisions” is not—your definition of reasonable and your client’s will never match.

Nanxi Liu, CEO at Blaze, describes her approach:

We explicitly communicate in our contract that if the project goes beyond the initial scope, the new requirements will be given a quote for the client to approve before implementation.

Nanxi Liu,

Blaze

Nanxi Liu,

Blaze

For productized services, this translates to:

What counts as a revision: Changes to existing work vs. new requests.

How many are included: Per deliverable, per month, or per project.

What happens after: Additional revisions billed at $X, or requires upgrade to next tier.

What’s explicitly excluded: Services you don’t offer, requests that don’t fit your packages.

Some productized services handle this with a simple clause: “Requests outside the scope of your current plan will be quoted separately. Work on out-of-scope requests begins only after written approval and payment.”

Payment terms: subscriptions, auto-renewal, refunds

Subscription billing creates legal considerations that project-based billing doesn’t have.

Auto-renewal: Most productized services bill on auto-renewal. Your ToS needs to disclose this clearly—many jurisdictions have specific requirements about how you communicate auto-renewal terms. Include how far in advance clients need to cancel to avoid the next charge.

Failed payments: What happens when a card declines? Most services retry a few times, then pause or cancel service. Spell out your process: “If payment fails, we’ll retry twice over 7 days. If payment still fails, your subscription will be paused and active requests will be held until payment is resolved.”

Refunds: Pick a policy and state it clearly. Options include:

No refunds: Service is non-refundable once the billing period begins.

Prorated refunds: Refund for unused portion of the billing period.

Satisfaction guarantee: Full refund within X days if not satisfied.

Credit-based: No cash refunds, but unused service converts to account credit.

Whatever you choose, the policy should match what your sales page promises. If you advertise a “30-day money-back guarantee,” your ToS needs to honor that.

Define “what happens when” for every scenario: cancellation mid-cycle, upgrade, downgrade, pause, and failed payment.

Designing SLAs for fixed-scope delivery

Service Level Agreements aren’t just for enterprise software. Any productized service making promises about speed, quality, or availability needs an SLA—even if you don’t call it that.

Your SLA defines what clients can expect and what happens when you don’t deliver. It’s a commitment device: it forces you to build systems that actually meet your promises, and it gives clients clear recourse when things go wrong.

Response time vs. turnaround time vs. resolution time

These three metrics sound similar but measure different things. Mixing them up in your terms creates confusion and disputes.

Response time: How quickly you acknowledge a request. “We respond to all new requests within 4 business hours” means someone on your team will confirm receipt and set expectations—not that the work will be done.

Turnaround time: How long until the work is complete. “Average turnaround is 48 hours” tells clients when to expect deliverables. Be careful with language here: “average” gives you flexibility, “guaranteed” locks you in.

Resolution time: How long until an issue is fully resolved. This matters most for services that involve troubleshooting, revisions, or back-and-forth. A design might be “delivered” in 48 hours but not “resolved” until the client approves the final version.

For most productized services, turnaround time is the metric clients care about most. State it clearly for each service tier:

Starter tier: 5 business day turnaround

Growth tier: 3 business day turnaround

Scale tier: 24–48 hour turnaround

Build buffer into your promises. If your team consistently delivers in 2 days, promise 3. Underpromise and overdeliver beats the reverse every time.

Setting measurable commitments by service tier

Your SLA should differentiate your tiers. If every tier gets the same service levels, you’re leaving money on the table—and giving clients no reason to upgrade.

Common SLA differentiators for productized services:

Turnaround speed: Faster delivery at higher tiers.

Queue priority: Higher tiers jump ahead of lower tiers.

Revision rounds: More included revisions at premium levels.

Active request limits: More concurrent work at higher tiers.

Support access: Slack channel vs. email-only, dedicated account manager.

Availability windows: Extended hours or weekend coverage for top tiers.

A content agency might structure it like this:

Tier | Monthly price | Turnaround | Active requests | Revisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Basic | $1,500 | 5 days | 2 | 1 round |

Pro | $3,000 | 3 days | 4 | 2 rounds |

Enterprise | $6,000 | 24-48 hrs | Unlimited | Unlimited |

For more examples of how productized services structure their tiers, see our post featuring productized service examples.

The key: every SLA commitment needs to be measurable. “Priority support” means nothing. “Response within 2 hours during business hours” can be tracked.

When (and how) to offer service credits

Service credits give clients something back when you miss your SLA. They’re standard in SaaS, less common in productized services—but they can be a trust-building differentiator.

How service credits typically work:

Trigger: You miss a defined SLA commitment (turnaround time, response time, uptime).

Credit amount: Percentage of that billing period’s fee (10–25% is common).

Cap: Maximum credit per period (usually 100% of that month’s fee—you don’t want to owe more than they paid).

Process: Client must request the credit within X days of the SLA miss.

Example language: “If we miss our stated turnaround time for a deliverable, you’re entitled to a 15% credit on that month’s subscription fee. Credits must be requested within 14 days of the missed SLA. Maximum credit per billing period is equal to one month’s fee.”

Service credits work best when:

your SLAs are clearly defined and measurable

misses are rare (if you’re crediting every month, fix your operations)

the credit amount is meaningful but not crippling

Some productized services skip formal credits and handle SLA misses case-by-case—a free extra deliverable, a partial refund, an extended subscription. That’s fine for early-stage businesses, but as you scale, having a defined policy reduces negotiation and sets expectations.

Intellectual property and deliverable ownership

IP ownership is where productized services diverge most sharply from SaaS. When clients buy software access, they don’t expect to own the code. When clients buy content, design, or strategy work, they usually expect to own what you create.

Your ToS needs to address two separate IP questions: who owns the deliverables you create for clients, and who owns the systems, templates, and processes you use to create them.

License vs. full ownership (and why it matters for your model)

There are two basic approaches to deliverable IP:

Full ownership transfer: The client owns everything you create for them. This is what most clients expect and what most productized services offer. Once you deliver the logo, the blog post, the video—it’s theirs. They can modify it, resell it, use it forever.

License grant: You retain ownership and grant the client a license to use the work. This is less common for custom deliverables but makes sense for certain models—stock assets, templates, or work you might repurpose.

David Kemmerer, CEO at CoinLedger, describes the SaaS approach:

The customer gets the right to use but the company keeps ownership… ‘limited, revocable, non-transferable’ right to access service.

David Kemmerer,

CoinLedger

David Kemmerer,

CoinLedger

For most productized services, full ownership transfer is the right default. Clients paying for custom work expect to own it. But you need to specify what triggers the transfer.

Common approaches:

Transfer on delivery: Client owns the work as soon as you deliver it.

Transfer on payment: Client owns the work once they’ve paid in full.

Transfer on approval: Client owns the work once they sign off.

“Transfer on payment” protects you if a client cancels mid-project or disputes a charge. They don’t own work they haven’t paid for.

Work-for-hire considerations

In the US, copyright initially belongs to the creator—unless the work qualifies as “work made for hire.” For work created by employees, this is automatic. For contractors and agencies, it requires a written agreement.

For productized services, you typically want the client to own the work. Your ToS should include clear work-for-hire language or an explicit assignment of rights.

Standard language might read: “All deliverables created under your subscription are considered work made for hire. To the extent any deliverable does not qualify as work made for hire, Company hereby assigns all rights, title, and interest in such deliverable to Client upon payment in full.”

If you use contractors to fulfill client work, make sure your contractor agreements include matching IP assignment language. You can’t transfer rights to clients if you don’t have them yourself.

Protecting your processes and templates

Here’s where productized services need to be careful. You’re assigning deliverable IP to clients, but you’re not assigning your business IP—the systems, templates, frameworks, and processes that make your productized model work.

Draw a clear line between:

Client deliverables: The custom work you create for them (they own this).

Your tools: The templates, checklists, SOPs, and systems you use to create that work (you own this).

Pre-existing materials: Anything you created before the engagement or use across multiple clients (you own this).

Example language: “Client receives full ownership of all custom deliverables created specifically for Client. Company retains ownership of all pre-existing materials, proprietary processes, templates, and tools used in creating the deliverables, including any improvements made during the engagement.”

This protects your ability to use your own systems with other clients. The blog post template you use, the design system you’ve built, the onboarding checklist you’ve refined—those stay yours.

Data handling and client access

Not every productized service touches client data. If you’re writing blog posts from scratch or designing logos based on a brief, your data exposure is minimal—just the project details clients share with you.

But many productized services require deeper access: login credentials to client systems, access to analytics dashboards, customer lists for email campaigns, or connections to client software via API. That access creates legal obligations you need to address.

When your service touches client systems or data

The first question: what data do you actually need, and how will you handle it?

Map out your data exposure for each service tier:

What client data do you receive? Names, emails, customer lists, analytics, credentials, financial data?

How do you receive it? Email, shared drive, direct system access, API connection?

Where do you store it? Your project management tool, cloud storage, local machines?

Who on your team can access it? Everyone, or limited to assigned team members?

How long do you keep it? Duration of engagement, plus some retention period, or deleted immediately after?

The answers shape your legal obligations. A service that receives customer email lists has different requirements than one that just gets brand guidelines.

Your ToS should include a section on data handling that covers:

What data you collect: Be specific about categories.

How you use it: Only for delivering the service, or for other purposes?

How you protect it: Security measures you have in place.

How long you retain it: And what happens to it when the engagement ends.

Who you share it with: Subcontractors, tools, third parties.

Data Processing Agreements for productized services

If you serve clients in the EU (or handle data of EU residents), GDPR likely applies to you. Even if you’re based in the US.

Under GDPR, there’s a key distinction between data controllers and data processors. Your client is typically the controller—they decide what data to collect and why. You’re typically the processor—you handle data on their behalf, following their instructions.

As a processor, you need a Data Processing Agreement (DPA) with your clients. This is a legal document that specifies:

Subject matter and duration: What processing you’re doing and for how long.

Nature and purpose: Why you’re processing the data.

Data types: Categories of personal data involved.

Data subjects: Whose data it is (your client’s customers, employees, etc.).

Your obligations: Security measures, confidentiality, deletion requirements.

Sub-processors: Any third parties you use to process the data (and how you’ll notify clients of changes).

For productized services, the cleanest approach is to create a standard DPA that covers your typical data processing activities, then make it available to all clients. EU clients who need it can sign it. Others can skip it.

Don’t bury data processing terms in your main ToS. Keep the DPA as a separate document—it’s easier to update when regulations change, and it signals that you take data protection seriously.

Security commitments you can actually keep

Your ToS will likely include some security representations. Make sure you can actually deliver on them.

Common security commitments for productized services:

Access controls: “Client data is accessible only to team members assigned to your account.”

Encryption: “Data is encrypted in transit and at rest.”

Password handling: “We never store client passwords in plain text; we use password managers and revoke access when engagements end.”

Breach notification: “We will notify you within 72 hours of discovering any data breach affecting your information.”

The 72-hour notification requirement comes from GDPR, but it’s a reasonable standard even for non-EU clients.

Avoid vague security language like “industry-standard security measures” or “reasonable protections.” These mean nothing and protect no one. If you can’t describe your security practices specifically, you probably need to improve them before making commitments.

Be honest about what you don’t do. If you’re a small productized service without SOC 2 certification or enterprise-grade security infrastructure, don’t pretend otherwise. “We implement security measures appropriate for a small business handling client marketing data” is better than promising Fortune 500-level security you can’t deliver.

International clients: compliance without complexity

Productized services attract clients from everywhere. Your website is global by default. That’s great for growth, but it creates legal questions that traditional local agencies never face.

The good news: you don’t need a law degree or country-specific contracts for every market. A few standard provisions handle most international scenarios.

GDPR basics for non-EU businesses serving EU clients

We covered DPAs and breach notification in the data handling section. Here’s what else you need:

Privacy policy: Publish one that meets GDPR standards (clear language about what you collect, why, how long you keep it, and data subject rights).

Lawful basis: Know why you’re processing data (usually “legitimate interest” for B2B services or “contract performance” for client work).

Data subject rights: Have a process for handling requests to access, correct, or delete personal data.

You don’t need to appoint an EU representative or register with data protection authorities unless you’re processing data at significant scale or handling sensitive categories.

For most productized services, GDPR compliance means having proper documentation and following reasonable data practices—not building an elaborate compliance infrastructure.

Jurisdiction and governing law clauses

Every contract needs to specify which laws govern it and where disputes get resolved. For productized services selling globally, this matters more than you might think.

Governing law: This determines which country or state’s laws apply to interpreting your contract. Most US-based productized services choose their home state: “This Agreement shall be governed by the laws of the State of Delaware, without regard to conflict of law principles.”

Jurisdiction: This determines where legal disputes get heard. You generally want disputes resolved somewhere convenient for you: “Any disputes arising from this Agreement shall be resolved exclusively in the state or federal courts located in Wilmington, Delaware.”

Without these clauses, a client in Germany could potentially sue you in German courts under German law. That’s expensive and unpredictable, even if you win.

Some international clients will push back on US jurisdiction. Enterprise clients especially may require their local law to apply. For standard productized packages, hold firm—your terms are your terms. For high-value custom deals, you might negotiate, but understand the risks.

Currency, taxes, and cross-border billing

Legal compliance isn’t just about contracts. How you bill international clients creates its own considerations.

Currency: Decide whether you’ll bill in local currencies or USD-only. USD simplifies your accounting but creates exchange rate uncertainty for international clients. Some payment processors handle multi-currency automatically.

VAT and sales tax: If you sell to EU consumers (B2C), you may need to collect VAT. B2B sales to EU businesses are generally VAT-exempt if the client provides a valid VAT number. US sales tax rules vary by state and are evolving for digital services. Consult with a tax professional, but don’t ignore this—penalties for getting it wrong add up.

Payment methods: Credit cards work globally, but some markets prefer local payment methods. Consider whether you need to support alternatives for key markets.

Invoice requirements: Some countries require specific invoice formats or information. Your standard invoice should include your business details, the client’s details, a unique invoice number, service description, and tax information where applicable.

For most productized services, the practical approach is:

bill in USD (or your home currency)

use a payment processor that handles international transactions

clearly state that clients are responsible for any local taxes

include VAT fields on invoices for clients who need them

work with an accountant who understands cross-border transactions

Exit rights and cancellation terms

Every client relationship ends eventually. Some clients outgrow your service, some downgrade, some disappear without warning. Your ToS needs to handle all of these scenarios cleanly—protecting both parties and minimizing awkward negotiations.

What happens when clients cancel mid-subscription

The most common exit scenario: a client cancels partway through a billing period. Your policy needs to address:

When cancellation takes effect: Immediately, or at the end of the current billing period? Most productized services use end-of-period cancellation. The client has paid for the month, they get the month. This avoids proration headaches and gives you time to wrap up active work.

Work in progress: If a client cancels with requests in your queue, do you complete them? Options include:

Complete all work submitted before cancellation notice

Complete only work already started

Pause immediately, deliver nothing further

The cleanest approach: “Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We’ll complete any requests submitted before your cancellation notice. Requests submitted after cancellation will not be fulfilled.”

Access to deliverables: After cancellation, can clients still access past work? If you use a client portal, how long do they have to download their files? Set clear timelines: “Following cancellation, you’ll have 30 days to download all deliverables from your client portal. After 30 days, your account and associated files will be permanently deleted.”

Refunds on cancellation: Tie this back to your refund policy. If you offer no refunds, say so clearly. If you prorate, explain the calculation.

Data portability and transition support

When clients leave, they often need help transitioning—especially if your service touched their systems or created assets they rely on.

Your ToS should specify:

What you’ll provide: At minimum, clients should be able to export or receive copies of all deliverables you created for them. If you have data they need (analytics, reports, credentials you managed), define how you’ll hand it off.

Format: Will you provide native files, PDFs, or both? For design work, does the client get the source files (Figma, PSD) or just exports? Be specific—this is a common point of conflict.

Timeline: How long after cancellation will you support the transition? “Data export requests must be made within 30 days of cancellation. We’ll provide requested files within 5 business days.”

Cost: Is transition support included, or does it cost extra? For standard cancellations, basic file handoff should be included. For extensive transitions—training a replacement, documented handovers, extended access—you might charge a transition fee.

Exit rights cut both ways. Clients need to know they can leave without losing their work. You need to know you won’t be supporting ex-clients indefinitely for free.

Protecting yourself from “take the work and run”

The nightmare scenario: a client gets a bunch of work delivered, then disputes the charge or initiates a chargeback. They keep the deliverables; you keep nothing.

A few protective measures:

Payment before delivery: For new clients especially, consider requiring payment before work begins. Subscription billing handles this naturally—they pay for the month before receiving that month’s work.

Ownership tied to payment: Your IP clause should specify that ownership transfers only upon payment. If a client doesn’t pay, they don’t own the work and don’t have rights to use it.

Chargeback language: Include terms that address chargebacks directly: “If you initiate a chargeback or payment dispute, your access to all services and deliverables will be immediately suspended. Any deliverables created during the disputed period may not be used until the dispute is resolved in Company’s favor.”

Termination for non-payment: Give yourself the right to terminate immediately if payment fails: “Company may terminate this Agreement immediately if payment is not received within 14 days of the due date.”

Another important one is document sign-off along the way. If a dispute does happen, you’ll need proof that you delivered what was promised. David Goodale, CEO at Merchant-Accounts.ca, who helps merchants fight chargebacks, recommends documenting client approvals throughout the project:

They’ve signed off on the font. They’ve signed off on the color. You would include that correspondence to show, hey, we worked with this person, and here’s them signing off on our work.

David Goodale,

Merchant-Accounts.ca

David Goodale,

Merchant-Accounts.ca

For productized services, this means keeping records of revision approvals, not just final delivery.

This documentation matters. One agency owner on Reddit shared what happened when a client disputed a $15,000 charge: “Stripe just went ahead and yanked that on out of my bank account the day before payroll.” She won the dispute—but only because she had a signed contract, a no-refund policy, and emails from the client approving the work.

These clauses won’t stop every bad actor, but they establish clear terms you can point to if disputes arise—and they give you grounds to pursue recovery if someone walks off with unpaid work.

Frequently asked questions

Can I use the same Terms of Service for all my service tiers?

Yes. Your ToS covers universal terms—payment, IP, liability, termination. Tier-specific details like turnaround times live on your pricing page and are incorporated by reference.

How do I handle scope requests that don’t fit my packages?

Three options: decline the request, quote it as a separate one-off project, or point the client to a higher tier. Don’t absorb out-of-scope work into existing packages.

Do I need different contracts for clients in different countries?

No. One ToS with proper governing law and jurisdiction clauses works globally. EU clients may need a separate Data Processing Agreement for GDPR compliance.

Should I offer refunds if clients aren’t satisfied?

That’s a business decision. Whatever you choose—money-back guarantee, no refunds, or prorated credits—state it clearly in your ToS and apply it consistently.

How often should I update my Terms of Service?

Review annually and update when you change service tiers, billing models, data handling, or markets. Notify existing clients of material changes at least 30 days in advance.

Build once, use forever

The legal work you do now pays off with every client you sign. One Terms of Service covers your next hundred customers. One SLA framework sets expectations across all your tiers. One IP clause protects your processes while giving clients what they paid for.

Traditional agencies spend hours on contracts for every engagement. You spend hours once, then point every new client to the same checkout page with the same terms.

Start with the minimum viable setup: ToS, privacy policy, clear scope. Add the DPA when EU clients ask for it. Formalize your SLA when you’re ready to make public commitments. Get a legal review when revenue justifies the investment.

Your productized service is supposed to be simpler than agency work. Your legal infrastructure should be too.

This guide provides general information about legal considerations for productized services, not legal advice. Laws vary by jurisdiction and business type. Consult a qualified attorney for advice specific to your situation.